Toward the end of the 1990s, my interest in the Armenian-American writer William Saroyan roughly coincided with the emergence in Istanbul of a new publishing house, Aras Yayıncılık (Aras Publishing). Aras's stated goals at the time of its founding in 1993 included opening a window into Armenian literature and serving as a bridge for the cultural legacy of Turkey’s Armenians.

To put it bluntly, Turkey's decimated Armenian community had largely—and understandably—kept its head down for many decades since the 1915 Genocide and as a result, its rich cultural legacy remained largely hidden from even the most "woke" and well-educated, well-read segments of the country's intelligentsia.

How does one address a near-complete void in the consciousness of the Turkish-speaking target audience, which, by the way, included many Armenians who could not speak or read their language and had grown up with Turkish as their mother tongue? Over the years, an eclectic selection has emerged: writers who are well-known to contemporary Armenian readers in Turkey, writers whose creative output spanned the middle decades of the twentieth century, writers who were killed in 1915, rural writers, urban writers, writers who joined the diaspora too young to remember an earlier life, writers who wrote primarily in the diaspora but whose imagination remained rooted in the land they had fled, and so on.

Of the very few Armenian writers who had been known to Turkish readers, William Saroyan was the most prominent—and for many, he was the only one they had read anything by. All his output had been in English, not Armenian. For those two reasons, he would not be an immediate priority for Aras, with its focus on creating translations from Armenian into Turkish (it does publish works in the original Armenian, but those are only about a third of the 200-plus books published so far) and bringing writers back from obscurity. That said, as the most famous Armenian writer in history, it was inevitable that he would be included in the roster at some point. As time went by, it would be odd if he were not.

As the publisher (a very small operation then, comprising fewer than 10 people who pitched in as their other commitments allowed, as it is now, albeit with some new faces) got ready to compile a first volume of stories, they bumped into me at the Istanbul Book Fair, and they happened to know my name at that point because of my having recently published a long (too long) essay on Saroyan’s life, work, his trip to his ancestral city of Bitlis and what it meant to him.

(The story of how that essay came about involves a colorful cast of characters including a Kurdish bear and is intertwined with my own, still continuing education on Turkey’s buried Armenian past. I wrote a long story on that as well, when a Turkish literary blog asked for a piece on Saroyan. “My Uncle Saroyan” was published on the thirty-ninth anniversary of Saroyan’s death. I don’t have an English translation; Google Translate isn’t too bad these days, though.)

One of the things in my article was an example of bowdlerization in the mid-20th-century Turkish translations of Saroyan’s work. An innocent phrase that referred to “Armenian, our beautiful language” had been cut from an otherwise faithfully translated paragraph. Perhaps on the strength of evidence of such expertise and diligent research on my part, Aras gave me the run of the Saroyan series as editor. They dismissed my concerns regarding a Turkish writer taking this on (were there really no qualified Turkish and English-speaking Armenians available?), pointing out that they had gone over the article carefully and I seemed to fit the bill. And I mean carefully; I later saw a copy that was highlighted and underlined with a ruler.

The staff did much of the work. I selected the content after the first two books, reviewed the translations along with the book editors, wrote introductions, and translated some of the Saroyan content, my favorites. There were also a couple specific things I wanted to bring to the table.

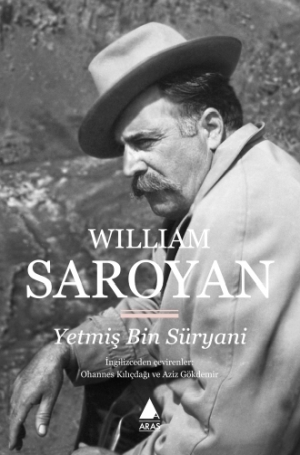

Publishing stories that had long been ignored in Turkey was one. The collection, My Name Is Aram, was well known, for instance, but Saroyan’s first book, still in print in the US, was not. “The Armenian and the Armenian,” a story whose last paragraph is often quoted by Armenians around the world, had been overlooked; it matched neither Turkey’s preferred historical narrative nor the carefully tamed “Anatolian Saroyan” image established by stories populated by farmers and families in California who “looked just like us.” There were early stories and even poems, bylined Sirak Goryan, largely unread by even Saroyan’s diminishing devotees in the US. They had been published in Hairenik, the Armenian-American publication, during a period that overlapped the well-known stories that built his reputation nationwide, and compiled by James Tashjian much later. We put those hidden gems, and much more, in a compilation we titled Yetmiş Bin Süryani, after a famous Saroyan story, "Seventy Thousand Assyrians."

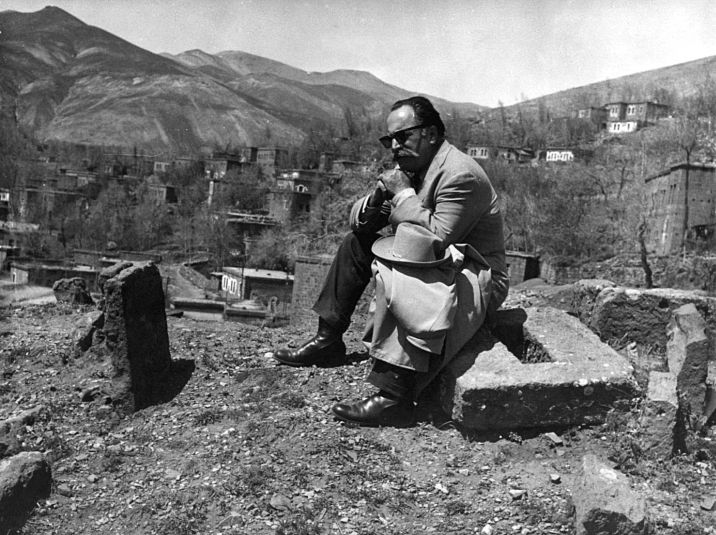

My second obsession was the play Bitlis, which Saroyan had written many years after his one-day visit to his family’s ancestral home on May 17, 1964. It wasn’t much of a play but rather a stream-of-consciousness elegy with real characters. The photos from that day, of which to me the most striking was Saroyan sitting among the ruins of the city’s old Armenian quarter, hinted at the turmoil knocking around his head that day, but for years we had ignored his own words on it. The play became the centerpiece of a book we put together for the Saroyan Centennial in 2008. We added recollections including Bedros Zobyan’s eyewitness account of the entire May 1964 trip from Istanbul to Van and back, previously available only in Armenian; interviews; and analyses by several writers and commentators including an essay by Professor Dickran Kouymjian on Bitlis as a cathartic play. We also snuck in the even longer, uncut version of my original “Saroyan in Bitlis” essay.

The covers of two books are below. So many memories are tied up in them.

The portrait on both covers is that of Saroyan in one of his many pensive moments during his 1964 trip. It’s mirrored in the iconic “among the ruins” photograph I mentioned above.

Saroyan in Bitlis (Fikret Otyam, 1964)

That, by the way, was not the cover of the first Aras edition of Seventy Thousand Assyrians. Since we were going back to very early stories and even poems, I had insisted on featuring a young Saroyan, minus the hat, the trenchcoat, the mustache. Professor Kouymjian had to comb through his boxes of Saroyan material to find a photo he remembered putting away half a lifetime ago.

The portrait of William Saroyan as a young man (Kourken of Pasadena, n.d., courtesy of Dickran Kouymjian)

After 2008, Aras published more Saroyan books, sticking to the canonical US volumes (one of which does feature the “young” photo above), so there was no need for me to be involved as some sort of curator. You can see the full run of books — and I hope there’s more to come — on their William Saroyan page.

P.S. If you want to see the bear but can’t be bothered to scroll through the Turkish article linked above, here it is:

Saroyan in Bitlis with the Kurdish dancing bear, empty “inje belli” tea glass in hand (Fikret Otyam, 1964)